Videos by American Songwriter

Van Dyke Parks may be one of the few acts at MoogFest you won’t see on stage with a Moog synthesizer. But that doesn’t mean the legendary songwriter, composer, arranger, pianist and performer doesn’t have a unique history with the instrument. “If anyone should be playing MoogFest, it’s me,” Parks says, half-joking, from his home in California.

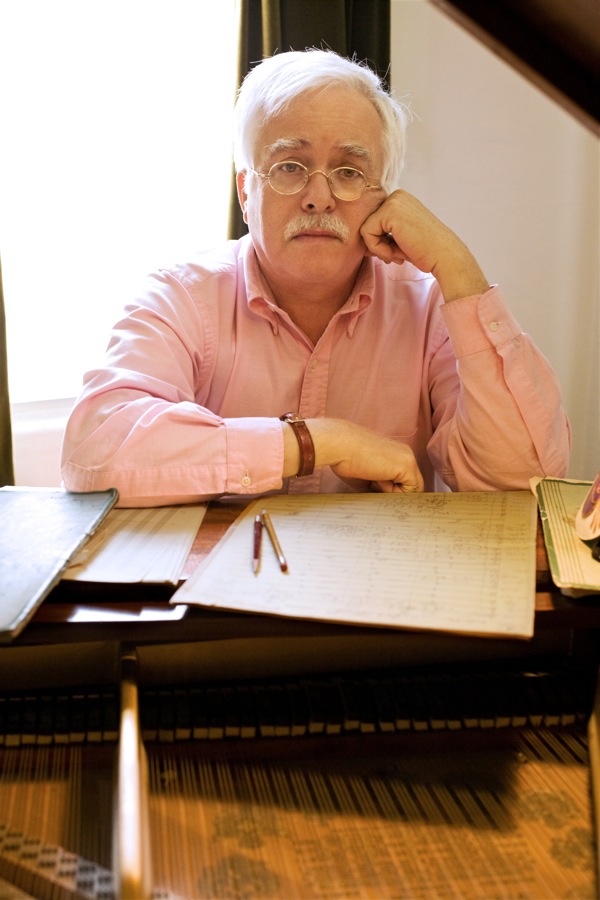

These days, Parks is most comfortable behind the keys of a grand piano, and for his MoogFest set, Friday night in Asheville, North Carolina, he will be joined by the group Clare & the Reasons. (They also play their own set before Parks’ slot.)

With Clare & the Reasons, Parks is out on the road playing songs like “Heroes and Villains” (from his collaboration with Brian Wilson, SMiLE), Clare’s “You Got Time,” and Parks’ own “The All Golden,” from Song Cycle.

In our interview below, Parks talks about his association with Moog, his influential first album, 1968’s Song Cycle, and working Joanna Newsom. Check out the audio clip of Parks’ Moog work from 1967.

[wpaudio url=”https://americansongwriter.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/08-Ice-Capades-1.mp3″ text=”Van Dyke Parks – Ice Capade #1″ dl=”0″]

What has been your connection with Moog?

I was one of maybe four people in Los Angeles who worked so hard to create a fluency in the language that Moog could produce. I was one of maybe four people who had a synthesizer in this town. The work I was doing in 1967, with the Ice Capades and AT&T commercials, I taught the machine how to say the words, “ice capades,” as the skater came close to the lens after an axel. I did that ad music because I was in an act of counter-culturalism. [Laughs] I wanted to prove that I could be commercial. So I did it with Moog and the fact is, I listen to it now, and when we go up to parking lots and, you see, the voice comes on and goes, [robot voice] “Please take the ticket,” and we make phone calls to business organizations and, rather than outsource, they’ll have a robot voice. This is all very ho-hum now, in the context of the age that we live in. But in 1967 and ’68, it was frontier activity, and it showed how hard I worked and how outside the box [I was] with Moog. That’s the truth.

Did you use a Moog on Song Cycle?

No, no. There was no Moog in my future work. The reason for that is, like the synthesizer, I saw so many people stampede to get their snouts in the trough; there was so much falderal, so much rush toward Moog, and later towards synthesizers, I decided not to go on the road more traveled. I believe that’s one of the reasons that my recorded work shows a real intense interest in analog, and the desire not to make a profit, but to put it all in the costs of the musicians who play. [Laughs] I’m famous for that. I pay for the music I make. But if I didn’t sacrifice for it, it would be worthless.

But Song Cycle is innovative in other ways – in the recording techniques, vocal effects and songwriting.

A book just came out on a series called 33 1/3 on Song Cycle. It really dishes the dirt in a great way. With Song Cycle, I am in awe of it as a collective gesture. I really think it’s a wonderful and beautiful piece of work. On the other hand, it’s safe to say, that I made every single possible mistake that could possibly be made by a person who wants to be sustained as a musician.

Why would you say that? Commercially?

Well, I think it was courageous, in fact. It was a hallmark of courage. I felt like I had a very short opportunity to show how much I wanted to learn. And I used it as an academic tool. I used the entire episode to learn, so that I could serve others in music, as well as to find some illumination. To me, Song Cycle turned on many lights and made it easy for other people to bore their way in.

It’s an incredible record.

I think it wanted to be beautiful. I wanted to make something that people would think was Faberge, a jewel of some sort, set well. I wanted people to love life because they had been through it. Although to tell you the truth, it’s filled with an almost psychotic despair on my part. I was recovering from some assassinations, on a presidential level, as well as the death of my own brother. Those things are reflected in the music. For example, in “The All Golden” you can hear the serenity, the funereal drum roll, reserved for the president of the United States, that accompanies the piece halfway through. So many of the influences of the record have to do with events of that time, as a good troubadour would want to record. I felt my obligation was to make a diary, a musical diary. That, in fact, ends up, in the long run, [to be] a monument of irrelevance. That’s what’s happened, it’s old news, but I’m glad that I went through it and I love it to this day. I never listen to it, of course, but I remember it. I have the music paper for it in my piano bench, it’s quite yellowed with age. I haven’t [yellowed with age], but it has.

People like Joanna Newsom were inspired by Song Cycle. Did working on the full orchestra arrangements for some of the songs on her album Ys remind you of Song Cycle?

Not really. I suppose in some way you could make a comparison or a commonality. I would say that it would be in that it was highly individual and reflective and more introspective than projected information. [Also] in its degree of fantasy – certainly on a very ambitious level of fantasy. In fact, I was deeply touched she asked me to do that record. We didn’t work together, per se. Arranging is a very monastic discipline. You can’t just say things are going to be purple and hum that. You don’t hum purple. You have to concentrate, you have to focus. I mean, I do. I have to be alone. It’s 180 from the extemporaneous process. I like both those worlds, by the way. I like tossing off a flip idea, with enthusiasm, sitting down and playing the piano. Things come from an unpremeditated group disorder. I like that a lot. My favorite rock and roll record, by the way, is [Music From] Big Pink. The Band plays a piece, but then they get away from the piece quickly. They each have a solo, a moment for a solo. They go absolutely ape-shit. Then, they go back to their modicum of decorum, when they get back to the chorus. In other words, they go nuts, they do all that, and then follow a very tightly-knit flight formation when they want to. So, you see, I love both those worlds: planning an event and letting it go. I like all of that. That’s far from your question. I enjoyed working for Joanna Newsom.

Tell us about the artists you’ve been working with lately, Clare & the Reasons, who will be playing with you at MoogFest.

Oh, I love these people so much. They are of a higher order, in terms of their humanity and grace. They are high people. The violinist from France, Olivier, masterful. Bob Hart, from New York. Then John Cottle is from London, he’s the cellist. I played with those people; they were so nice when I showed up. For the first time we tried this, up in Seattle, doing a show to see if we would get through it, they invited me to be with them on this. As a matter of fact, the reason I did end up coming [on tour] was that as much as anything, I just love these people. I love playing with them, they’re great people. It’s even fun being in a band with them. It’s a rough-and-tumble tour, it just gives us a chance to get together before we record. I’m going to have them do my next album with me in March. So this is kind of a chance for me to get my land legs.

What else are you going to do in Asheville?

I’m going to see Billy [Edd] Wheeler. He’s the titan of living songwriters who have a decidedly Appalachian stance – that Celtic thing that arrives from mountain men who precede satellite radio. And he’s one of them, and he’s incredible and I’m very excited that I’m going to see him. The last time that I saw Robert Moog was in Asheville, at a music festival, standing next to John Hartford. That’s an indelible memory, because John Hartford gave my son his reflections on bluegrass. My son was doing his high school dissertation. He had to write this paper on bluegrass. He called up John Hartford to speak with him. And [Hartford] did so for about half an hour, although he could not hold the phone, because he was so ill. He soon died. His wife held the phone. So when I look at John Hartford and Robert Moog standing there together, I think a lot about some wonderfully contributive people, and I’m very happy to come back to Asheville.

Van Dyke Parks plays MoogFest on Friday at 11 p.m. at Asheville’s Thomas Wolfe Auditorium.

2 Comments

Leave a Reply