Videos by American Songwriter

Marty Stuart’s Grammy-winning song “Hummingbyrd,” an instrumental tribute to The Byrd’s guitar virtuoso Clarence White, stood in stark contrast to the other Nashville-produced country records at the 2011 awards show. Mick Conley, who engineered the album at Nashville’s RCA Studio B, says, “If you listen to ‘Hummingbyrd,’ it’s not perfect. But it’s a performance. It’s real people.”

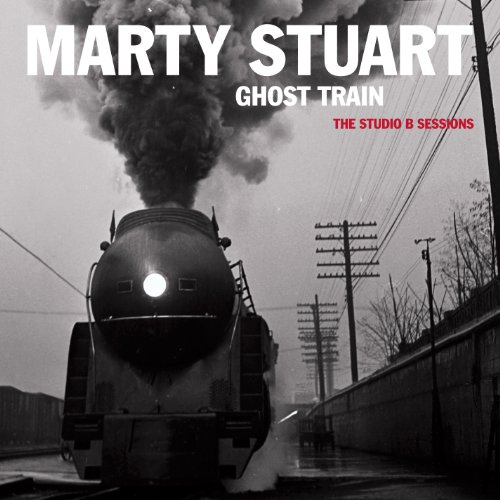

On Ghost Train, Marty Stuart wanted to capture the feel of classic country bands like Buck Owens and The Buckaroos and Merle Haggard and The Strangers, and so he and Conley looked no further than the room where Elvis, Roger Miller, and The Everly Brothers had made so many classic records.

“There’s something magic about the bleed you get in a room – if you can deal with it. Back in the heyday, they played very quietly, with everybody in the same room.”

Mick Conley first came to Nashville in the 1980s, a time he recalls as a transition period for Nashville. “Everybody had to play direct,” says Conley, admitting that while the players remained great, guitar tones suffered due to being recorded directly into the recording console, without amps. Each player was sequestered in his or her own room, making it easier for an engineer to fix things later on.

With “Hummingbyrd,” Conley says, “We could have made it perfect. Chopped it up and replaced everything. But, there are very few fixes, very few overdubs on that record.”

Recording at Studio B like they did in the golden era of country was a daunting task. “The good news is I know the history of the place. The bad news is I know the history of the place and it’s pretty heavy,” says Conley. So before the actual sessions, Conley, Stuart, his wife Connie Smith, his band The Fabulous Superlatives, and several other engineers made little pilgrimages to the studio to take notes. Conley says they spent a lot of time walking around the tracking room, clapping their hands, and just listening.

“At the end of the day, you have to get over being a fan of the studio and what’s been done there. At a certain point, you gotta say, ‘Okay, I gotta get to work now.’”

That kind of respect for Studio B, along with Stuart’s deep history with the place (he’d made his first recordings there as a 13-year-old backing up Lester Flatt), helped the Ghost Train team capture some of that lost magic. And, today, the album stands right alongside those classic country recordings.

Conley says the secret to working in Studio B is in a back-to-basics approach and an open mind. “You can’t let the room be anything else than what it is,” he says. “Some of those tracks, like ‘Hummingbyrd,’ sound like it’s raging loud and the trick is they used little Fender Princeton amps. Marty and I were talking about this – it’s almost a jazz technique, where the great jazz musicians can be extremely intense but really quiet. And that’s hard to do.”

Following his “let the room be what it is” mantra, Conley set up the band almost exactly as they play live. He made small adjustments and rolled with the punches, bit by bit rethinking the way most engineers are used to recording in high-tech studios these days.

“Harry Stinson on drums in center, Kenny Vaughan on one side, Marty on the other side,” Conley remembers about their setup from Studio B. “I actually set the bass player Paul Martin up in the center facing the drums so that it would bleed into everything evenly. So you start rethinking placement. Same with the steel players. I set them up so when they bled it would bleed to the side that I would naturally mix them in. It’s a really different way of going about these things – kinda like the old school.”

Going in there with that kind of reverence and love for the place really helped the whole attitude.” Plus, adds Conley, to make a classic country record the band has got to be sharp. Stuart and the Superlatives nailed each song after only a few takes. After three or four sessions at Studio B, tracking for the album was in the can. “Marty would play and sing at the same time. It’s just about [it being] a totally live record. That was the whole process – going in with a great band and just playing.”

Conley started out as a jazz guitar player but says he was always attracted to sounds. “Even being a guitar player, sometimes it was more about how you got the sounds than the playing,” he says.

A big part of capturing sounds is finding the right audio tools and a few years back Conley made a discovery when he saw an ad for a small Portland, Oregon-based audio company called ADK Microphones and called up the company’s founder, Larry Villella.

“We had a lot of the same ideas about sound. He’s really familiar with a lot of good vintage mics and what’s quirky about them,” says Conley about Villella. “If you take the quirkiness out of the old gear and try to make it better, then you’ve got nothing. Then you’ve got no character. We started talking about those kinds of things.”

Conley bought a few ADK mics and Villella, in turn, asked Conley to offer his expertise in ADK’s product design.