Videos by American Songwriter

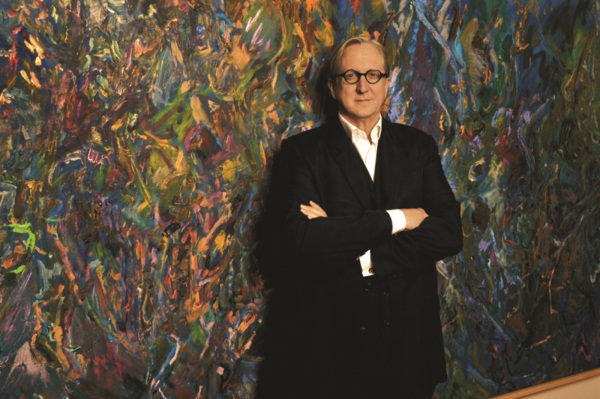

Over the course of 40 years in the music industry, T Bone Burnett has made a lot of friends in high places, producing albums for artists as varied as Robert Plant, B.B. King, Tony Bennett, Elvis Costello and Willie Nelson. Last year, he got many of them together for a good cause, creating the three-city Speaking Clock Review tour to raise money for The Participant Foundation, which supports the inclusion of music and arts education in public school systems, among other causes. This fall, he released a live album that includes performances from Costello, Gregg Allman, Neko Case, John Mellencamp, Elton John & Leon Russell, and Ralph Stanley to keep the fundraising going. We talked with Burnett about the project, his producing style and the current roots music revival.

How did the Speaking Clock Revue come together?

It started because I was at a screening of the movie Waiting For Superman at a friend’s house and was talking with the filmmakers and Jeff Skoll of Participant Media. It’s an interesting 21st Century media company in that a big part of its mission is devoted to charity, or the redistribution of wealth. The whole center of their company is a database of two million activists gathered through the films it makes. It made films like An Inconvenient Truth and Food Inc., a lot of interesting documentaries. It also makes good fiction like Syriana and Good Night And Good Luck. The company was putting out this film [Waiting For Superman] on the state of public education, so we decided to put together a short tour to benefit it.

What inspired you to get involved in supporting music education in schools?

It’s something that’s been a concern of mine for a long time. Here we have the 3 Rs – reading, writing and arithmetic. The Greeks had the 3 As – academics, athletics and arts. Plato said that education stands on those three legs. Without any one of those three, education will fall down. In this country, the arts are the first thing eliminated, especially in public schools. What they’ve found is when the arts are eliminated, children get bored and tired of school. When the arts are included, children’s imaginations are allowed to run wild.

Whenever so many talented artists come together, there are always some surprises. What was the most unexpected thing for you on the tour?

The most surprising thing to me in the whole show was Ralph Stanley getting up with one acoustic guitar and a string bass and completely flooring the whole place. He was the most hardcore rock and roll star of them all.

Are there any artists you’re targeting for future Revues that you couldn’t get this time?

I’m working with young folk artists. I did some of that on this edition with The Punch Brothers, for instance. That’s one of the most incredible bands this country has ever produced. Chris Thile, their mandolin player, is probably a once in a century musician, like Louis Armstrong was a once in a century musician. Chris is one of those kind of cats.

What other young artists do you like?

I like The Cave Singers. I love Arcade Fire and My Morning Jacket. I love the Decemberists. I think Colin Meloy is a serious American writer.

The artists you were able to get to perform speak to the respect people have for you as an artist and a producer. Do you have an overarching philosophy when it comes to producing?

I’ve been through so many different stages in my own life. The thing that’s been consistent all the way through it is that at the base it’s storytelling. All record making, all songwriting, all singing is storytelling. I’ve always tried to keep that in mind. First, you look for the voice.

So you focus mostly on the vocals rather than the music or the sound of an album?

The sound of the music is completely dependent on the sound of the voice. That’s reality. The instruments are more or less the same. The human being is completely different. Of course, I don’t mean all instruments are exactly the same. There are great and bad sounding instruments, but even bad ones can make a beautiful tone. The person and the voice are so distinct that it changes the way you make sound out of either good or bad instruments. It’s about blending the instruments with the tone of the voice.

It seems like the public has become a lot more interested in roots music over the past decade than it was in the ‘80s and ‘90s. What do you attribute that to?

There are a couple of big trends going on in the world. One is toward globalization, the other is localization or tribalism. This is the music of our tribe. The Scots-Irish, Black people, Italians, the people that came here and started cooking up this music. I think things have gotten very depersonalized in the modern world. It started in the 20th century, the century of the self. This is a way to touch base. These songs are hundreds of years old, but they’ve been rewritten and have grown into all kinds of things.

Does roots music speak to a longing for something more authentic?

I think there’s always that. My view is that we live in a very de-authenticated world, especially in music. All music has been de-authenticated because it has been compromised so heavily by current technology. We’re still using the MP3 format, which is really attached to the dial-up modem. It’s completely outdated technology. We’ve already outgrown it. We’ll be in 5G in a couple of years. There’s no reason to have degraded audio.

Do you think technology has been bad for the music industry?

The access [technology] offers is beautiful. The communication is good. I’m not a Luddite. I want to move on to the next thing. I just worked with a band called The Civil Wars. They’re incredibly good and they have the benefit of it all. Today, we have access to everything.

We need to work something out so musicians can get paid. Last year or the year before, Google billed $30 billion in advertising. Nine percent of that was driven by music searches. Musicians deserve part of that $30 billion, just like radio shares part of its advertising revenue with songwriters.

What’s happening now is similar to what happened to the music industry in the 1920s. In the 1920s, when radio proliferated to big cities, the record industry collapsed. That’s why they began recording all this [roots] music. Before that, it was classical and show tunes. When that collapsed because radio was playing it for free, they went down south where people didn’t have electricity and recorded those songs with a pulley system. The original country songs were recorded without electricity.

3 Comments

Leave a Reply