Videos by American Songwriter

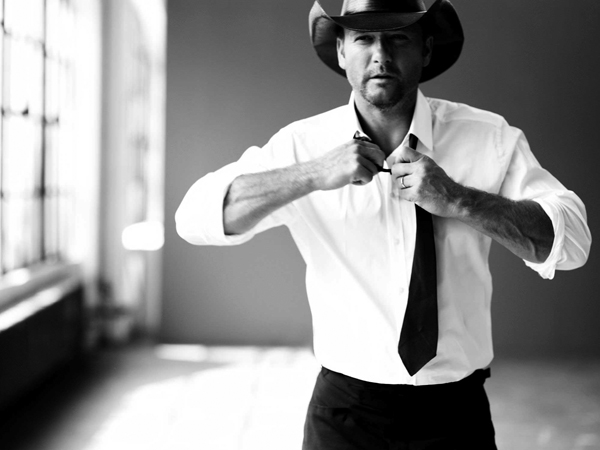

(PHOTOS: Danny Clinch)

Explore the May/June Issue

On the day he moved to Nashville, Tim McGraw stepped off a Greyhound bus with a guitar and a suitcase.

He arrived inauspiciously around 3 a.m. on May 9, 1989, and checked into small room at the Hall of Fame hotel, a few blocks off Music Row. The next morning, he went downstairs and started drinking beers – and more importantly, buying beers.

At the hotel bar that day, the 22-year-old hopeful crossed paths with Tommy Barnes, the songwriter who played him a novelty number, “Indian Outlaw.” And he met Craig Wiseman, the songwriter who forged a close relationship with McGraw by writing future No. 1 hits such as “Live Like You Were Dying,” “Everywhere,” “The Cowboy In Me” and “Where The Green Grass Grows.” With a friendly face and a running tab, McGraw quickly built a close circle of allies in the Nashville songwriting community, like Mack Vickery, Wayne Perry and “Wild” Bill Emerson.

Of course, success didn’t happen overnight. McGraw’s first day in Nashville took a turn for the worse when one of his musical heroes, Keith Whitley, was found dead at age 34. A few weeks later, McGraw went broke and had to move out of the hotel and onto a former fraternity brother’s couch.

Although the money had run out, his luck didn’t. Today, McGraw can boast 37 million albums sold and 45 Top 10 country hits – including 23 chart-toppers. He’s also a Grammy-winning fan favorite who has relied almost exclusively on outside material to build his impressive catalog.

In a rare and exclusive interview with American Songwriter, the Louisiana native discusses the hits that made him a superstar, as well as his early musical heroes and his favorite duet partner, his wife Faith Hill. And now that he’s free from his longtime contract with Curb Records, he drops a hint at what lies ahead.

Click here to read American Songwriter‘s list of the best McGraw songs.

What did you hope to achieve when you got to Nashville? What was your ultimate goal?

I was playing clubs at home and I wanted to come and be a country star. That’s what I wanted to do. I wanted to play country music. Songwriting wasn’t the main focus. I mean, I was writing songs. Those first two or three years, I had written a couple hundred songs with writers all over town. They’re floating around out there somewhere. A couple may be good but most of them were awful. I really wanted to be an artist and get an artist deal.

Who were your heroes back in those days?

If I had to pick two, I would pick Merle Haggard and Bruce Springsteen. Those were my songwriting heroes.

Did you ever cross paths with Harlan Howard back then?

No, I never met Harlan. When I first moved to town, those kind of guys were around everywhere. I was sort of … drunk most of the time [laughs].

Did you hang out with songwriters a lot in those early days?

I hung out with Tommy Barnes all the time and “Wild” Bill Emerson, who wrote a lot of Hank Williams Jr. stuff. Wayne Perry and I hung out a lot together. There was a group of us – Kenny Chesney, Tracy Lawrence – that got together.

Did you write with them, too?

Yeah, we wrote. I don’t remember any of it but we wrote. I was actually performing some of the songs Kenny was writing. Back then, Kenny, Tracy and I would run around together and I never thought of Kenny wanting to be an artist. I don’t think he ever said much about wanting that. I think he was concentrating on songwriting back then. And he’s a really good songwriter, by the way.

How did you find songs for your first album?

When I got my record deal, I was running around with Byron [Gallimore, his longtime producer] listening to songs. Of course, being a new artist and being with Curb Records, nobody knew who I was. Curb was sort of new in town at the time. It was tough to get good songs played for me. So when it came down to recording, I didn’t have any say-so in the songs. I had “Indian Outlaw” but I wasn’t allowed to do it. The label didn’t like it and one of my producers, James Stroud, didn’t like it. Byron liked it but James didn’t like it.

Do you still like that song?

Yeah, I think that song … how do I say it … sort of changed what I thought I could do. I don’t look at it as high art, but I do look at it as a moment in time that defined what I could do in my career and where I could go … And then “Don’t Take the Girl” came right behind it. Remember, “Achy Breaky Heart” had just come out, so when “Indian Outlaw” came out, people thought, “Oh, here’s another one of these guys who has another one of these kinds of songs, so it’s going to be a moment in time and then it’s going to go away.” I think “Indian Outlaw” started my career and could have ended my career if I didn’t have “Don’t Take The Girl.”

13 Comments

Leave a Reply