“They still call Woodstock ‘sex and drugs and rock and roll,'” he said. “Which it absolutely wasn’t. It was much more. It was a new world.”

It’s already been seven years since Richie Havens died. He was only 72. Yet no once since has ever made a sound quite like his. The voice, the soul, the joy, the rhythmic, percussive groove of his guitar playing, all of it came together to create music unlike any other.

Videos by American Songwriter

Who else, for example, could take “Here Comes The Sun,” a universally loved (or as close as can be). perfectly written and rendered song. After all, it’s by George Harrison and The The Beatles. It doesn’t get better.

And as any singer or musician knows, to cover a Beatles song – any Beatles song – is not unlike covering a Stevie Wonder song. In that nobody can do it better. Stevie and The Beatles both created the ultimate record of their songs; it’s not something which can be surpassed.

But with a singularly soulful voice, great joy and love of songs and songwriting, and an excellent producer and team of musicians, it is possible to record a Beatles song and bring it somewhere else, not better than The Beatles, but truly great. There are many more examples which disprove this contention than those which confirm it. But some do exist: Joe Cocker’s “She Came In Through The Bathroom Window” is one. As is Richie Havens’ “Here Comes The Sun.”

His greatness with this – and other famous songs he didn’t write – seemed to do with a lack of ego on his part, no sense of a singer trying to prove something. The spirit in that record and all of his music is connected not to ego, or any other motive except for a genuine connection with the greatness of song. There in the delicate, brief passage of time in which George Harrison captured his unfettered feeling of pure exultation at the end of a long, cold winter and the sparkling start of Springtime, signalled by something nobody in England had seen for seeming eons: sunshine.

It’s a song about hope: hope that we can endure even through the coldest, darkest seasons of our lives. And like the greatest of the great songs, it endures more than 50 years now since its creation precisely because it is pure: it is the songwriter’s authentic celebration of our early progression through time, but with the knowing that the sun hasn’t abandoned us forever – as ancient man feared after seemingly endless periods of frozen darkness – but would return, and in time all would rejoice that, at long last, the ice is slowly melting.

It’s all there, and Richie channeled the joyous essence of the song, making it his own without obscuring any of its greatness. Into the record and his performance he injected his singular soul, inspiration, faith, joy, love (for man, the earth, and humanity’s ability to translate our lives into art). He supported it humbly but beautifully, with his inimitable percussive guitar groove and the gravitas of that venerated voice of the ages, a force of nature, the sound of a human expressing real love.

When I was notified that he accepted an interview request back in 1993 to line up with an L.A. trip, I was thrilled, of course. But admittedly a tad worried, as in other instances, that the man in person would not match the magnitude of that beloved spirit. It’s not a random thought. Many times in this work there’s been an unexpected distance between the real guy and the ideal we all hold. It’s understandable and not uncommon.

But quite often comes the happy realization that the guy is authentic. That the purity of the soul and joy expressed in the music is not phony. John Prine was that, as was Tom Petty, James Taylor, Leonard Cohen, Laura Nyro and some others.

Richie Havens, as the world has known for decades now, was no phony. He was the real deal. We met in the loud chaos of downtown L.A. He was dressed in white, saintly robes, as if about to take the Woodstock stage again, and exuded a zen calm. There are some folks who are so grounded that they put you at ease immediately. He was that.

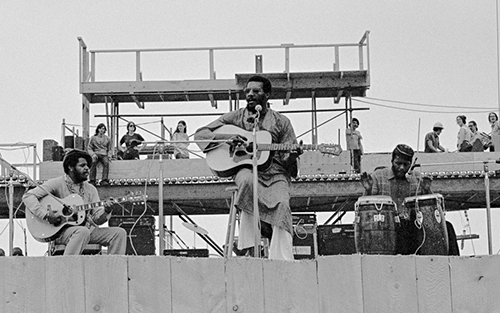

Famously, he was the first artist to perform at Woodstock, and for circumstances unforseen as he took the stage, he played longer than any other performer too.

When asked how he would explain the spirit of that time – the Sixties – to those kids born long after, he smiled. He looked off towards the sky for a moment, and then said, softly, “I would tell them it was a time when people became better people. People became more open people.”

It’s an answer that was essentially Richie: positive, loving, and spiritual. It wasn’t about the free sex, the mud, the crowds or the chaos. It was about the music. And about hearts opening to the force of love.

Born in 1941, he grew up the eldest of nine kids in the Bedford-Stuyvesant projects. Long before he ever played guitar he was a singer. And a good one – he sang doo-wop and was naturally gifted at hearing and singing harmony. Doo-wop was acapella street singing, four singers or so doing it all with vocals – melody, harmony, groove.

The guitar came into his life when he wanted to add percussion to these proceedings – he did think of it as a percussion instrument first – and instinctually he developed the fiercely dynamic and unique rhythmic attack which distinguished his music.

He was also a gifted visual artist as well, and was great at sketching portraits. He could make some real money in Greenwich Village doing this for hours. It was money he’d put into music. Also food, as he found it almost as necessary for survival as music. Though it never started with any serious professional aspirations, he realized he could do this thing in a professional way – as were others right there in the village. So he decided to see what might happen if he sang at one of the many “hootenanny nights” in the clubs there, which were similar to the open-mic nights we all know. A chance for beginners to begin.

He got to know Dylan as a friend before he ever heard his music. Or so he thought. He had heard and learned to play “A Hard Rain’s A’Gonna Fall,” by Dylan, which he learned at a Hoot night by a performer. He had no idea who wrote it. He added it to his repertoire, and played it one night when Dylan was there. When informed that the songwriter of that on4e was in his audience, Richie was pleasantly surprised, because he didn’t know his soft-spoken friend was a songwriter at all, and certainly not one who could write something at that level.

But it didn’t matter in terms of propriety to him. To Richie, songs were about the joy that unified people. They weren’t about publishing, hit records, radio play, record deals or any other real-work commercial concerns.

“That’s how we were back then,” he said. “It didn’t matter who wrote it. We were all sharing.”

It was Albert Grossman, Dylan’s manager, who offered Richie a contract, but the artist wasn’t sure he wanted to label himself a folksinger, since he loved and sang all kinds of music. But he wisely went through that door, and though his music transcended any easy genre classification, he could play the part of folksinger as good if not better than anyone, given the irrepressibly genuine passion he could stir up solo, just one voice and a guitar.

That betterment of humanity he attributed to the spirit of the Sixties was embodied by his music, and especially his historic performance at Woodstock. It was August of 1969 and it was one of the first-ever music festivals of the time. As our pal Henry Diltz, the official Woodstock photographer told us, nobody had a clue that it would become as huge as it did. But masses of people arrived, so many that nobody could get in or out as all traffic access was blocked.

“We were right in the middle of it,” remembered Henry, “but there was no way of knowing the size of the thing from where we were onstage, and backstage. We had no idea of just how massive it was until the next day when the New York Times had a photo taken from a helicopter above, and we saw our tiny island of a stage surrounded by thousands of people in every direction, like the size of a little town.”

So expansive was the town that Henry, like many, who had a motel room quite close to the festival, never used it once, as any attempt to exit and then return was out of the question.

Rickie wasn’t slated to open Woodstock. And certainly no one ever invited or expected him to play for three hours. But the helicopters above were incapable of bringing in the rock bands that were set to follow.

So being Richie Havens, he did solo what most artists never could. He kept going. He famously rose to the challenge and let the spirit guide him.

It’s all there in the movie: he strung together folk songs and hymns and more. Then he decided to wing it. To wing it at Woodstock, all alone, movie crews shooting, lovers making love on the lawn, children dancing and playing, hippies tripping, copters circling overhead. It was like an Apocalypse Now of music and love instead of war and madness.

Remarkably, he created the astounding “Freedom,” an epic about this unbound spirit of the Sixties, right there on the remarkable spot.

“I was supposed to play fifth!” he said, but was told they needed him, because none of the bands could get in and the show was already an hour late.

He didn’t warm to the idea immediately. He said, “So you want them to throw beer cans at me for the show being an hour late?” Not me, buddy.”

Yet they persuaded him, and all alone, he faced the unprecedented ocean of people, and made history.

“I got onstage and I started talking fast,” he said. “Then I started talking about what a beautiful day it was and how we finally conquered being swept under the rug. I made up ‘Freedom’ then because I didn’t have anything else!”

When he talked about Woodstock, he was quick to avoid revisionist thinking.

“We were showing numbers [the media] couldn’t hide anymore. We were showing solidarity they couldn’t hide. Woodstock was about something no one could control because it was a cosmic accident.”

But that guitar style – where did it come from? And what makes it sound the way it sounds?

It’s an open tuning, he said, D major. He figured that out when he was a kid, and used it ever since.

“I realized this is six strings,” he explained, “which could equal six guys in a doo-wop group. So now I’m the lead and this is my back-up. I laid it flat on my lap and put my thumb across it like a bar, and chunked along like a dulcimer. I am a frustrated drummer. I think that is really the sense of music, the drums. I am playing drums on guitar, that is what I do.”

He so invested himself into every song he sang that even the songwriters were stunned. When Dylan heard him perform “Hard Rain,” he approached him afterwards, at Folk City, with tears in his eyes.

“He came up to me,” Richie said, “and he was a little high. He said, ‘Man, you’re my favorite player of that song. You really play that song!’ I had no idea he wrote it!”

Unafraid to take on a famous song, his choice of “Here Comes The Sun” was an easy one to make.

“I needed a happy song,” he said. “A happy song that said something, and is universal. It says this is where we are, but we’re gonna be all right.”

Though he often performed dark songs, his outlook was decidedly sunny, as was his message of enduring faith.

“The media tries to keep us back there,” he said. “They try to make it seem as if the Sixties was the only time that happened. Yes, it was the only time since the Twenties that an entire generation spoke out. But since then it’s been a constant growth of that. Nothing’s changed. Nothing shifted. They still call Woodstock ‘sex and drugs and rock and roll.’ Which it absolutely wasn’t. It was much more. It was a new world.”

One Comment

Leave a Reply