This article appears in the July/August “British Issue,” now available on newsstands.

Videos by American Songwriter

Released as a single in October 1977, “Holidays In The Sun” by the Sex Pistols is a caustic punk bugger-off that kicks off with the sounds of hundreds – thousands? – of jackboots goose-stepping in unison. That short, sharp sample establishes the cadence of the song and hints luridly at its subject: the cultural arms race between the East and the West during the waning years of the Cold War.

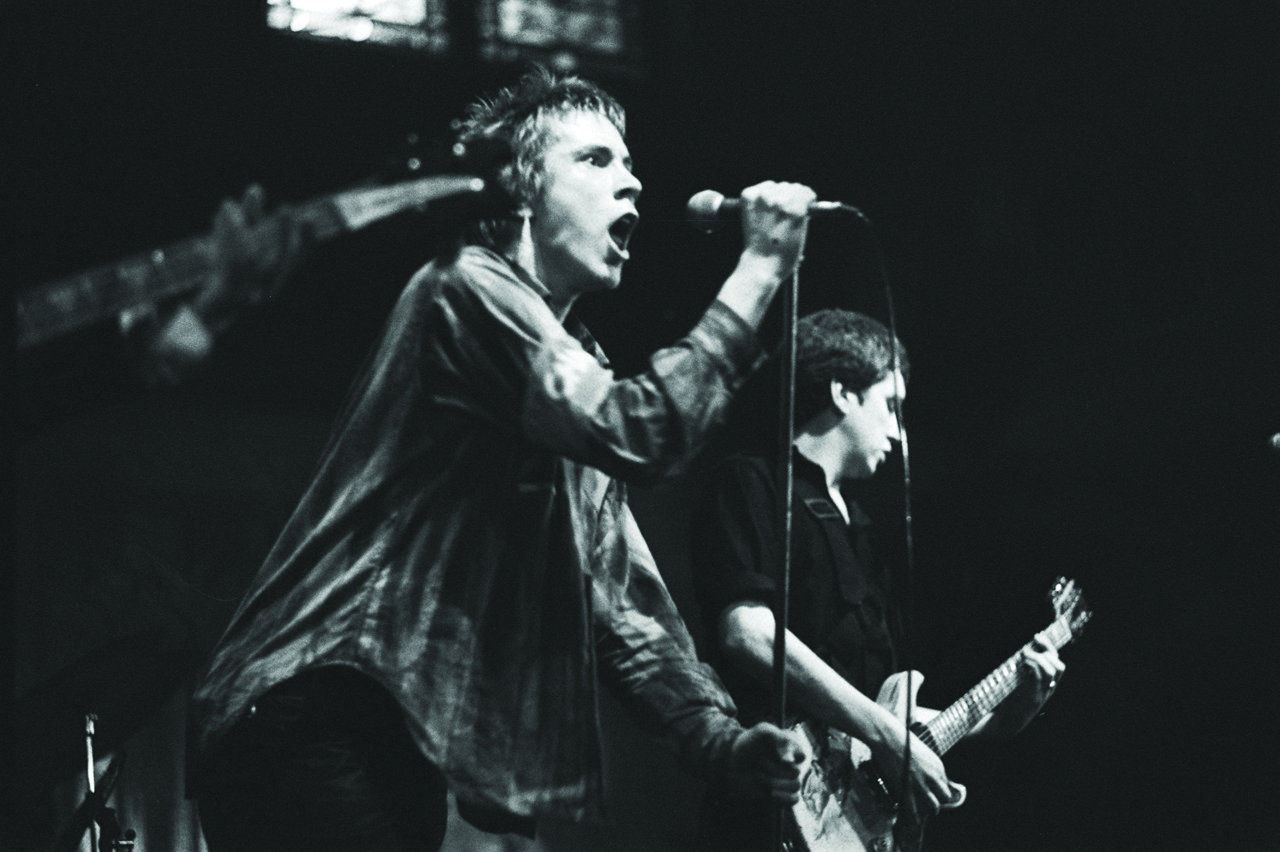

“I don’t wanna holiday in the sun, I wanna go to new Belsen!” declares Johnny Rotten (née Lydon). “I wanna see some history, ‘cause now I got a reasonable economy.” Meanwhile, Steve Jones pounds out a guitar riff that descends vertiginously, as though tracing the downward route of all empires. The band’s attack gains ferocity with each note, and Lydon’s vocals grow more and more unhinged. By song’s end he’s left babbling about the Berlin Wall and all the commies and capitalists who might be peering over it at each other.

How do you make sense of all the grotesque history that created these two oppositional forces? “Holidays In The Sun” has plenty of prickly attitude but no pat answers, primarily because the Sex Pistols knew there weren’t any to be had – at least none that satisfied Lydon. During these three-and-a-half minutes, the Berlin Wall is the only border in the world that matters, a metaphor for itself. To the east there is austerity and compliance; to the west, freedom and decadence.

What makes the song more than an angry tirade is the Sex Pistols’ willingness to implicate themselves in this volley of vitriol. They wrote the song following two very different retreats – first to the beaches of Jersey, and next to West Berlin, which they found much more welcoming in its debauchery. As Lydon writes in his new memoir, Anger Is An Energy, “You couldn’t escape the vibe: the war, and then the Wall, with the Russians staring over the top. West Berlin was all set up to annoy the East. It was glorious, but a bonkers, crazy universe. Readily available was everything and anything that would keep you up all night. Between the British and American soldiers, they had the place well sussed … Well done, the West, that’s what you’re tormenting the Russkies across the border with. This is freedom! What you got?”

Even as it draws from personal experience, “Holidays In The Sun” sounds like two fingers lifted in the air, a defiant raspberry blown at the establishment. It’s not only one of the best songs to emerge from the U.K. punk scene, but arguably the most politically brutal single ever to crash the charts. Just thirty years after the greatest-generation heroics of World War II, the U.K. was mired in a crippling economic depression. Unemployment and inflation both soared, while trash piled in the streets of London, uncollected and rotting. Even if the empire had entered a period of tentative recovery by 1975, that depression had already left a lasting impression on the punk generation.

Most of the Sex Pistols’ peers were similarly angry and radicalized. The Leeds outfit Gang of Four borrowed their name from a faction of the Chinese Communist Party; the Clash literally called for a white riot; and X-Ray Spex recorded the skronking proto-riot grrrl anthem “Oh Bondage Up Yours.” Even Joy Division’s inner anguish sounded like a manifestation of national ills, and Elvis Costello’s disgusted missives against TV detective shows and Top 40 radio had the spark of social dissent, if only because they narcotized audiences to the very real problems affecting recession-era Britain.

No longer content with playing the same old blues-based riffs on the same guitars, bands like Wire, The Slits, The Pop Group, and The Clash borrowed from the styles and traditions brought to England by immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean, including reggae and dub, Afropop and funk. The lyrics might be cryptic, but the music was inherently political and leftist, as it expressed solidarity with colonial immigrants at a time when nationalists were calling for closed borders. If the future no longer looked promising, the punks would make the most of the present.

I’m So Bored With The U.S.A.

Meanwhile, in America, The Dead Boys and The Ramones were wearing swastikas onstage.

If the Sex Pistols were queasy about the rift between East and West, it appeared as though their U.S. counterparts had erased those distinctions altogether, sporting fascist iconography that either marked them as Nazi sympathizers or implied a kind of fatuous confrontation. They weren’t the only punks with swastikas (even the Pistols’ Sid Vicious had one emblazoned on his ripped t’s), but The Ramones in particular had a very conflicted relationship with the imagery – and not merely because frontman Joey Ramone (née Jeffrey Ross Hyman) was Jewish.

Like many of their peers, they borrowed the symbols from the nihilistic biker flicks of the previous decade, whose antiheroes were decked out in Kaiser helmets and Iron Crosses. The Ramones perhaps adopted the insignia via Arturo Vega, the artist who created their famous presidential seal logo and reportedly decorated the band’s apartment with Day-Glo swastikas. But much of that irony was lost from studio to stage, especially when it was accompanied by so many songs about violence. The band’s first and most famous song, “Blitzkrieg Bop,” was named after a German battlefield tactic that translates to “lightning war.” The Ramones sang songs about chainsaw massacres and baseball bat beatings, most of which either takes place on the movie screen or in the schoolyard – as though life were an EC Comic book or a horror movie.

Many critics have addressed the discomfort of a beloved band like The Ramones brandishing such thoroughly distasteful insignia, but “people who have written about punk have by and large tended to go to great lengths to dismiss, underplay, minimize, and even ignore the fascist iconography in the punk scene,” writes Nicholas Rombes in his 33 1/3 book on The Ramones’ self-titled debut. “On their first album, the Nazi references (and other references to violence) might be ironic, or they might not be. Their power lies in precisely this ambiguity.”

That instability was crucial to U.S. punk’s power in a country and a city that was politically and economically precarious. New York in the 1970s may have been worse than even garbage-strewn London, with large swathes of buildings all but abandoned to decay and squatters. Other bands translated their environment into music that sounded bombed out, but what’s remarkable is how many artists saw in it the foundation for a new way of playing pop music. Patti Smith and Richard Hell both married punk performance with poetry, guitar feedback with Rimbaud. Television abstracted everything into curlicue guitar riffs, while the Talking Heads scavenged African pop music but largely skirted the political ramifications. The world had already been ripped up, so all you had to do was start again.

American bands were generally more skeptical of prosperity than of poverty, which means the second wave of punks coming of age during the Reagan Administration were much more politicized. Hardcore bands like Black Flag and, yes, Reagan Youth criticized the President in loud, fast, violent songs that distilled angst and anomie down to its bluntest sentiments. “When cowboy Ronnie comes to town, forks out his tongue at human rights,” sings Jello Biafra on the Dead Kennedys’ “Bleed For Me.” “Smile at the mirror as the cameras click, and make big business happy.”

The most famous song in this punk subgenre came from perhaps the least likely source. In 1986, more than a decade into their career, the Ramones unleashed the angriest and most explicitly political statement of their career, “Bonzo Goes To Bitberg.” Anchoring their underrated 1986 album Animal Boy, the song draws its energy from a very real incident. Shortly after he started his second term, Reagan made an official visit to Kolmshöhe Cemetery in Germany, which contains the decorated graves of fifty Waffen-SS officers.

Even a band of dudes who had once sported swastikas found the visit infuriating, and Joey Ramone’s disgust remains potent thirty years later: “There’s one thing that makes me sick, it’s when someone tries to hide behind politics.” He spits the verses out with disgust, then leans hard into the chorus as the rest of the band comes up behind him with some grandiose power-pop ba-ba-ba’s. The Ramones turn an ugly incident into something almost beautiful and certainly transcendent, as though music was their only refuge from a world that made no sense.

A generous listener might interpret the song as a direct refutation of their casual display of fascist symbols a decade earlier, which wouldn’t be incorrect. The song is all the more damning from a band that never wanted to grow up, that only reluctantly stopped sniffing glue to sing about the world around them. If the Ramones had once thrived on instability, then punk in its last breaths was bemoaning that precariousness. “Bonzo Goes To Bitberg” is the sound of a band bravely trying to right the world.

One Comment

Leave a Reply