This article appears in the September/October 2015 issue, now available on newsstands.

Videos by American Songwriter

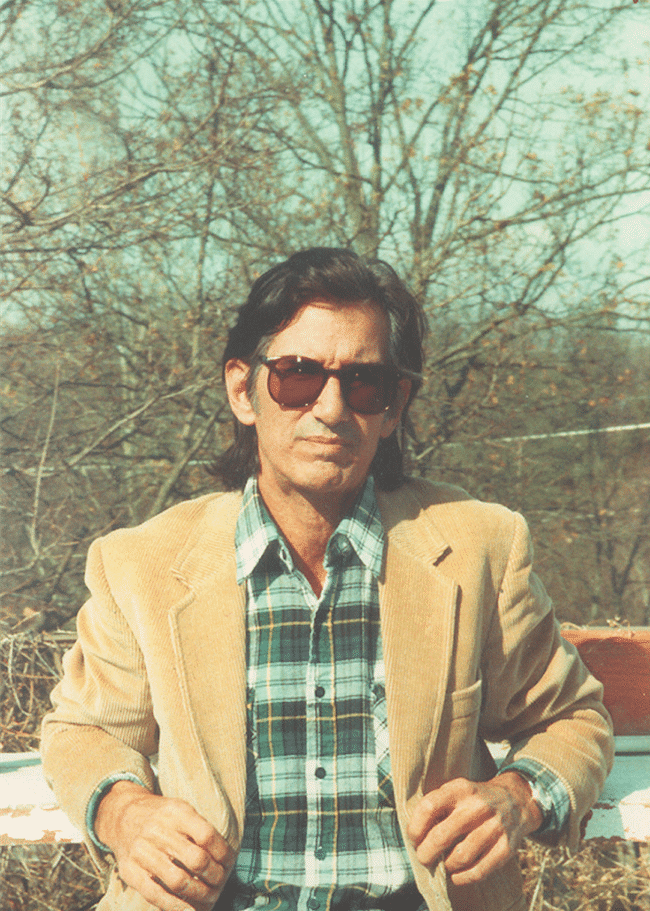

Long before the whole world woke up to the fact that Townes Van Zandt was a genius songwriter, other songwriters knew it. Willie Nelson, Emmylou Harris, Jerry Jeff Walker, Mickey Newbury, Doc Watson and Waylon Jennings all knew. They recorded his songs and sang his praises. Steve Earle said it best and most famously: “Townes is the best songwriter in the world, and I’ll stand on Bob Dylan’s coffee table in my cowboy boots and say that.” Since then, the world’s caught on.

Born on March 7, 1944, he died on New Year’s Day of 1997. The cause of death given was a mish-mash of problems stemming from years of addiction. But during those short 53 years, he wrote songs as deep and beautiful as any written before. He made 11 amazing albums. The author of the mythic and mystic “Pancho And Lefty,” he was a master at talking a simple folk narrative and imploding it, infusing it with history, mystery and poignant humanity, but always with simplicity and grace.

He didn’t seem to have a great drive to market himself, or get too deeply entwined in the music industry. But he loved writing and singing songs, and so was not unhappy when famous friends like Emmylou Harris, Waylon Jennings and Merle Haggard all recorded “Pancho And Lefty.” His place as a legend was secure while he was still alive, and he went on to write countless classic songs, including “If I Needed You,” and “To Live Is To Fly,” both of which are country standards.

He liked to make fun of death, so that when his own came, it was tough to accept. Not only did he name one of his albums The Late Great Townes Van Zandt, he would often scoff at death in songs, though suggesting sometimes it would be preferable to other life options. He died on the same day Hank Williams died, which has a sad poetic rightness Townes would have liked.

I interviewed him in 1990 and asked about the writing of his most famous song.

“I was in Dallas,” he said, “in a hotel room. That one kind of came from not having anything to do and sitting down with the express purpose of writing a song. I took one day and then I played what I had that night at a gig. And a songwriter told me, ‘Man, that’s a great. But I don’t think it’s finished.’ So I went back to my hotel room the next day and wrote the last verse.”

That last verse is an overview, told after the story is over. It jumpcuts into the future to look back at the outlaws as myth: “Now the poets tell how Pancho fell/ Lefty’s living in a cheap hotel.”

He spoke of the most important aspects of a song. “The one priority that I have is to keep [the song] simple. To keep it as perfectly bare and simple as possible. And get it down.”

I asked him if he came up with a good idea, if he’d write it down. “Yes, always. If it’s a good line and I’m driving, I’ll store it away. If I’m around a guitar, I’ll do it right away. Sometimes it can be a whole song and a whole verse. The core of the song will come through all at once. When that happens, I get some paper and pencil and write it down.”

But as with “Pancho And Lefty,” the song isn’t over after the initial charge of inspiration. He admitted to healthy revision always, with strong focus on the choice of every word: “Sometimes songs get real changed around. There’s always changes to be made, even little changes, like putting an ‘s’ on a word. That’s where my poetic background comes in. It seems a lot of people in Nashville write by phrase, or by the line, as opposed to writing by the word. A lot of my best songs are where every single word is where it’s supposed to be. Whereas a lot of country songs are more like everyday conversations.”

He spoke lovingly of writing songs, of the mystery he’s happy to embrace, and the exhilaration of feeling like a channel, bringing a song through from another place. But how does a songwriter get to that place when songs come through?

“You have to be alone,” he said softly. “You have to be ready for that. I’ve had songs that have intruded on whatever is going on. They usually come in the form of one line, which you might have to remember and go get later. But you have to allow yourself quiet time to be alone and think.

“I usually just tinker with the guitar. I have lines come at many different times that can turn into songs. Whole songs come, melody and words, when your mind is free. You can be thinking about the utility bills and the rent and write a certain kind of song. But you can’t think about the utility bills and write ‘To Live’s To Fly.’”

Asked about the ongoing challenge of being an artist in an industry, he said, “You might spend a little time just making sure you don’t get totally ripped off. Other than that, in my case, I just spend amazingly little time worrying about that stuff. When I write, it’s just between me and the cosmos. The only person I have to answer to about my songwriting is myself.”